It is known that many of the world’s languages are constantly slipping into extinction, particularly in an age of globalization in which the world’s major languages dominate international interchange.

Hebrew, the language of the Bible, never became extinct, but rather was mainly the language of Jewish study, prayer and scholarly texts. In their long exile, the Jews in the main adopted the languages of their host countries as their everyday means of communication. They also “invented” Judaic languages of their own, based to a great extent on the languages of their domiciles. The two most known of these are Yiddish of the Ashkenazi Jews of middle Europe, and Ladino, the Spanish-based language of the Jews who were expelled from Spain.

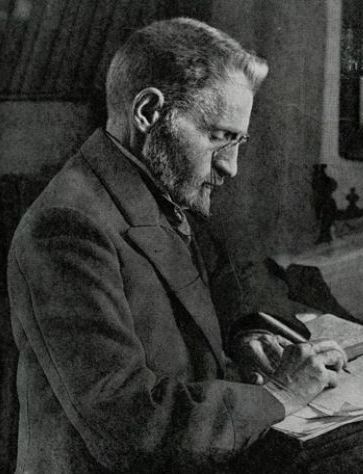

That Hebrew became again a spoken, living language and the main language of the modern State of Israel is due to a great extent to the single-minded determination of a man named Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the driving spirit behind the revival of the Hebrew language in the modern era.

Born as Eliezer Yitzhak Perelman in 1858 in Luzhki, Belarus, in 1858, he attended a traditional Jewish school, where he studied Hebrew and the Bible from the age of three. He then went on to a yeshiva (school of higher Jewish education). Eventually, Ben-Yehuda transferred to a Russian school and became obsessed with modern Hebrew literature, eagerly consuming Hebrew periodicals, especially those concerned with Jewish nationalism. For Ben-Yehuda, nationalism became a way to embrace Hebrew without religion.

In 1881 Ben-Yehuda immigrated to Palestine, then ruled by the Ottoman Empire, and settled in Jerusalem. He found a job teaching but also set out to develop what was in effect a “new language” that could replace Yiddish and other regional dialects and become a means of everyday communication between Jews who emigrated from various regions of the world. Ben-Yehuda regarded Hebrew and Zionism as symbiotic. He created the first modern Hebrew-speaking household and raised the first modern Hebrew-speaking child, Ben-Zion Ben-Yehuda.

Ben-Yehuda set himself to the task of creating new words for the modern world, based on the root forms or analogous concepts that could be found in classic Hebrew and other Semitic languages. He was also the editor of several Hebrew-language newspapers. The ultra- Orthodox Jews living in Jerusalem, for whom Hebrew was used only for holy purposes such as studying Torah, saw through Ben-Yehuda’s guise. Sensing his secular-nationalist intentions, they rejected him and his language.

Ben-Yehuda was a major figure in the establishment of the Committee of the Hebrew Language (Va’ad HaLashon), later the Academy of the Hebrew Language, an organization that still exists today. In 1910, Ben-Yehuda began publication of his dictionary, but the full 17-volume set of the Complete Dictionary of Ancient and Modern Hebrew wasn’t completed until well after his death. Many of the words Ben-Yehuda coined have become part of the language, but others were not accepted by the general public.

Ben-Yehuda did not live to see the creation of the State of Israel. He passed away in 1922, only one month after the British authorities declared Hebrew to be the official language of the Jews of Palestine. Yet his dream of the nation of Israel in its own land, speaking its own language, came to fruition. His efforts are counted among the great language revivals of human history.