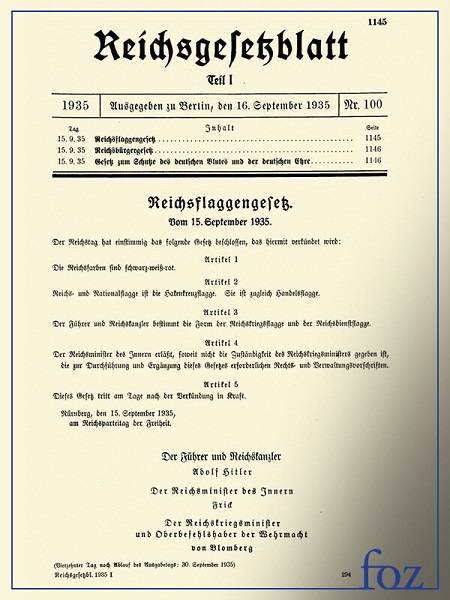

The Nuremberg Laws, enacted by the German Reichstag (Parliament) on Sept. 15, 1935, were racially discriminatory, anti-Semitic laws meant to institutionalize the Nazi program to persecute Jews. They were a continuation of earlier anti-Jewish measures enacted following the Nazi rise to power in 1933.

The Nuremberg Laws were the harbingers of much worse, harsher measures to come. They were enacted by the Reichstag at a special meeting convened during the annual Nuremberg Rally of the Nazi Party (NSDAP). The two laws were the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, which forbade marriages and extramarital intercourse between Jews and Germans and the employment of German females under 45 in Jewish households; and the Reich Citizenship Law, which declared that only those of German or related blood were eligible to be Reich (German) citizens; the remainder were classed as state subjects, without citizenship rights.

A supplementary decree outlining the definition of who was Jewish was passed on Nov. 14, 1935. The Nuremberg Laws defined as a Jew anyone who had three or four Jewish grandparents, regardless of whether that individual identified himself or herself as a Jew or belonged to the Jewish religious community. Even people with Jewish grandparents who had converted to Christianity were defined as Jews.

The laws were expanded also that month to include Romani people – known at the time as “Gypsies” – and black people. This supplementary decree defined Romanis as “enemies of the race-based state”, the same category as Jews. Prosecutions under the two laws did not commence until after the 1936 Summer Olympics, held in Berlin. Chancellor Adolf Hitler did not want international criticism of his government to result in the transfer of the games to another country.

The Nuremberg Laws had a crippling economic and social impact on the Jewish community. Persons convicted of violating the marriage laws were imprisoned and subsequently sent to Nazi concentration camps. Non-Jews gradually stopped socializing with Jews or shopping in Jewish-owned stores, many of which closed due to lack of customers. Many middle class Jews were forced to take menial employment. Emigration was problematic. By 1938 it was almost impossible for potential Jewish emigrants to find a country willing to take them. Starting in mid-1941, the German government started mass exterminations of the Jews of Europe.

In 1937 and 1938, the government set out to impoverish Jews by requiring them to register their property and then by “Aryanizing” Jewish businesses. Ownership of most Jewish businesses was taken over by non-Jewish Germans who bought them at bargain prices. Jewish doctors were forbidden to treat non-Jews, and Jewish lawyers were not permitted to practice law.

Like everyone in Germany, Jews were required to carry identity cards, but the government added special identifying marks to theirs: a red “J” stamped on them and new middle names for all those Jews who did not possess recognizably “Jewish” first names — “Israel” for males, “Sara” for females. Such cards allowed the police to identify Jews easily.

It was only the beginning of the oppression that led to the mass murder of Jews that was unprecedented and that has become known as the black mark in history called the Holocaust.